What happened to San Jacinto Day?

And why do Texans care more about the Alamo?

Raúl A. Ramos

April 21, 2023

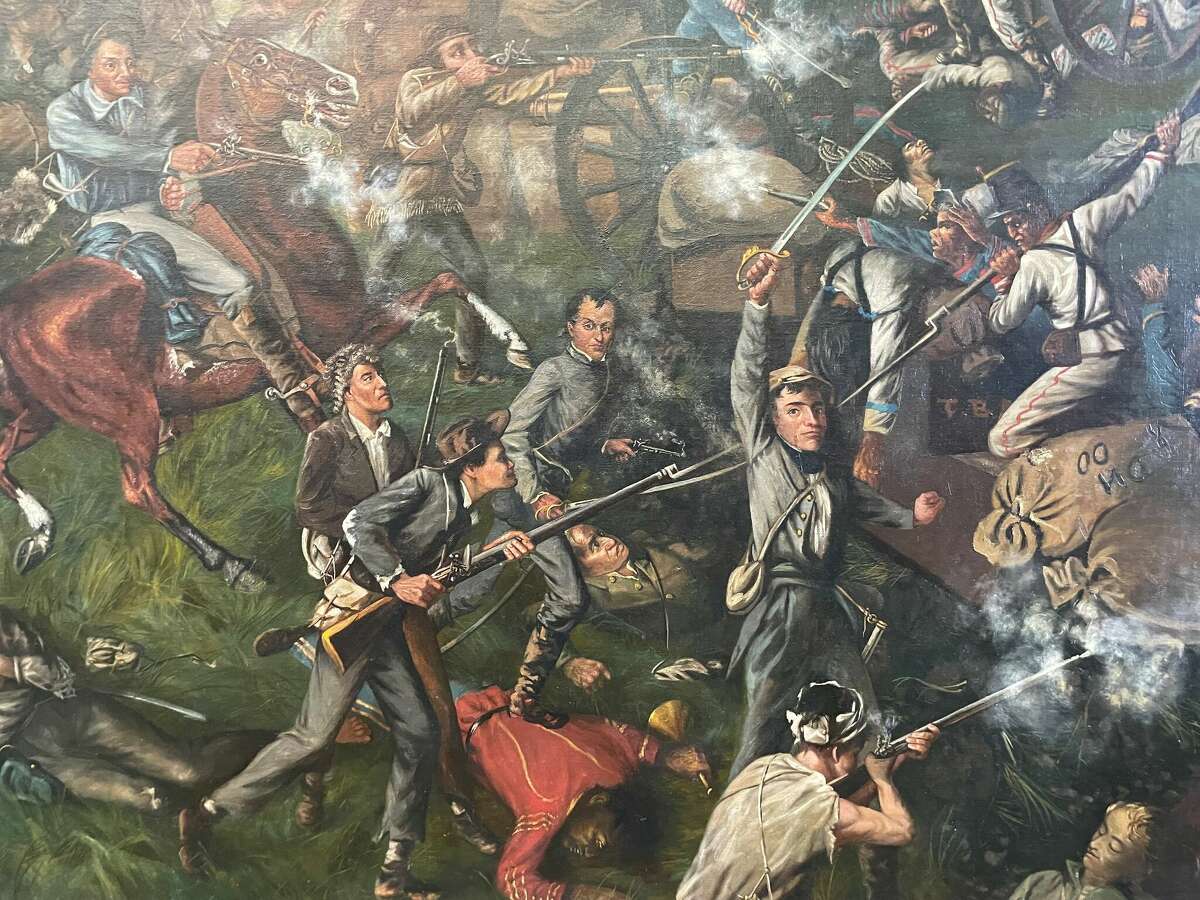

A detail from William McArdle’s “The Battle of San Jacinto,” which hangs in the Texas Senate. The battle was one-sided: 630 Mexican troops died, but only nine Texians.

Today is San Jacinto Day. On April 21, 1836, in a prairie next to what’s now the Houston Ship Channel, Sam Houston’s troops won the battle that seceded Texas from Mexico. But strangely, the Alamo — a battle that the Texians famously lost, and which wouldn’t be remembered were it not for the later victory at San Jacinto — has eclipsed San Jacinto in public memory. How did that happen?

In the decades following Texas Independence, the Battle of San Jacinto burned brighter in the popular imagination. Unlike the Alamo, San Jacinto represented a victory, and had living Texian veterans to tell the story. Made a state holiday in 1874, San Jacinto Day was a business and school holiday, celebrated across Texas with parades, speeches and school pageants. Texian veterans of the battle were honored, and they gave their recollections of that day.

That story was one of a complete slaughter of the Mexican troops, encamped on a marsh surrounded on three sides by the bay. The number of casualties reveal the one-sided nature of the rout. Approximately 630 Mexican troops were killed and 730 taken prisoner; only nine Texians perished. The conflict was so lopsided that I’m not sure the title “battle” is appropriate.

Numbers alone soften the vengeful violence fueling the Texian attack. We know this because the veterans described the yells of “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” while the shots rang out. The Mexican conscripts were to pay for Texan defeats.

The San Jacinto Monument and the Fred Hartman Bridge in the background, photographed Saturday, Aug. 13, 2022, in La Porte.Jon Shapley/Staff photographer

The killing continued unabated even as the Mexican soldiers dropped their weapons and ran, many drowning in the bayou instead. One veteran described Gen. Thomas Jefferson Rusk’s failure to spare the life of Gen. Manuel Castrillon, who was known for his desire to limit Santa Anna’s brutality. Texian soldiers ignored Rusk’s command and killed him. A battlefield surgeon recalls seeing Mexican soldiers with up to five bullet wounds.

Standing before the same Senate chamber for San Jacinto Day in 1907, Texian veteran Alonzo Steele recounted his experience. “They stood about two volleys and broke and ran and we pursued them some distance,” he recalled. He then added, of the hundreds of Mexicans taken prisoner, “Every man wanted one to take home as a servant!” For years, humiliated Mexican soldiers toiled in slave-like servitude after the war, some taken as far as Mississippi by returning volunteers.

But over time, as veterans of the battle of San Jacinto died off, fewer people told its story — maybe because being associated with a vengeful slaughter doesn’t make people feel great about themselves. Over time, attention turned to that earlier battle, one that helped justify the Texians’ fury at San Jacinto: the Alamo.

A detail from William McArdle’s “Dawn at the Alamo” — which hangs in the Texas Senate — shows a Mexican soldier preparing to stab William Travis in the back.

Lisa Gray

Between 1895 and 1905, the Irish-born artist Henry McArdle painted the mural-sized depictions of both the Alamo and the Battle of San Jacinto that adorn the back wall of the Texas Senate chamber. “Dawn at the Alamo,” which depicts the moment of pitched battle as the Mexican Army breaches the walls, is the more dramatic one. Next to it, “The Battle of San Jacinto” seems more like a clinical schematic representation. Its subtitle, “Retributive Justice — The Triumph of Texas Independence,” makes the case that because of the Alamo, the slaughter was deserved.

In the early 20th century, the story of the Alamo echoed Southerners’ “lost cause” framing of the Civil War. In 1915, D.W. Griffith’s production company famously released the movie “Birth of a Nation,” which showed the Ku Klux Klan in a heroic light. It immediately followed with a Texas drama titled “Martyrs of the Alamo,” which portrays the Mexican Americans living in San Antonio as untrustworthy drunks.

“Martyrs of the Alamo” is hard for me to watch. And looking closely at McArdle’s “Dawn at the Alamo” — at the faceless Mexican hordes storming the Alamo walls and stabbing William Travis in the back — I sense he is channeling the same raw anger and emotion.

After “Martyrs” came a slew of dime-store novels, movies and TV shows about the Alamo. From John Wayne to Billy Bob Thornton’s portrayal, the sacrifice at the Alamo has delivered the justification for revenge at San Jacinto.

But we no longer dwell on the Battle of San Jacinto itself. Since the American Revolution, American culture and politics prefer to associate with the underdog while unironically also playing the role of a superpower — and the impulse of Texan mythology is much the same.

Though the celebration of San Jacinto Day has receded into the background, unfortunately its spirit of retribution has not. How many of our lawmakers like to consider themselves Travis, standing on the wall against invaders? The cold, calculated conclusion of the war still echoes in our legislative houses.

Gov. Greg Abbott’s declaration of an “invasion” and proposed legislation to create a “Border Protection Unit” invite vengeful retribution at the border. House Bill 20 goes as far as permitting the unit to deputize citizens without training to support operations. Much like Gen. Rusk at San Jacinto, state authorities will be helpless to stop the fury anti-immigrant rhetoric has unleashed.

Raúl A. Ramos is an associate professor of history at the University of Houston and recipient of the T.R. Fehrenbach Book Award for “Beyond the Alamo: Forging Mexican Ethnicity in San Antonio, 1821-1861.”